The True Tragedy of Richard III is a play that is not often discussed outside of its relationship to Shakespeare’s play or the text as it appears in the original quarto printing. But what fascinates me the most about this play isn’t the printed text, but the story it’s telling – or rather, the story it tells and the story that the play’s frame narrative wants you to believe. While Richard still goes on his murderous rampage to get the throne – a story consistent across historical accounts from the period as well as in fictionalized depictions – he is not the same character who Shakespeare famously depicts. The Richard of True Tragedy experiences remorse for his actions throughout the play, and – most significantly – he is not disabled.

The narrative of True Tragedy opens with a dialogue between Truth and Poetry which covers the events that led up to the play’s action (an early modern “Previously on,” if you will). To Poetry’s question, “What maner of man was this Richard Duke of Gloster?,” Truth replies that he is “A man ill shaped, crooked backed, lame armed, withal, / Valiantly minded, but tyrannous in authoritie.”[1] Based on this description, the Richard audiences are primed to expect is a man differently abled; however, the body of the play does not mention Richard’s disability at all, with a single exception: the arrest of Hastings, during which Richard claims that the Queen and Shore’s Wife enchanted his arm (a declaration which similarly occurs in Shakespeare’s play).

But this is not the only part of the narrative which counters the frame: the leading role in pushing against the Tudor narrative is taken, not by Richard, but by his Page. The Page plays a unique role in the story, acting as both Richard’s confidant and as the interface with the audience. Brian Walsh argues that the Page’s language “invites the audience [ . . . ] to employ its interpretive power, soliciting the audience to draw its own conclusions about Richard.”[2] This is true throughout the play; as the audience’s interlocutor, the Page provides playgoers with an outside view of Richard’s mental and physical state. Of the characters in True Tragedy, only the Page expresses any sympathy for Richard – and his sympathy is consistently expressed in his speeches to the audience.

The Page’s narrative power is also apparent in his final appearance; directly after Richard and Richmond’s fight (which ends in Richard’s death), the Page speaks to Report, providing a record of what occurred during the Battle of Bosworth Field. In his retelling, the Page emphasizes Richard’s military prowess and bravery on the field by comparing his fallen master to the Greek hero Achilles, emphasizing that, despite his exhaustion, “worthie Richard [ . . . ] did neuer flie, but followed honour to the gates of death” as he prepared to fight Richmond.[3] By describing Richard in this way, the Page is, as Robert D. Stefanek notes, depicting his master as “a noble anachronism” who is “brave, honorable, and undaunted, not so much defeated as struck down by an adversary when caught at a disadvantage.”[4] Immediately after the Page’s version of events, playgoers are presented with the official Tudor narrative, which labels Richard as a traitor to Richmond, orders his body to be “drawne through the streets of Lester, / Starke naked on a Colliers horse,” and concludes by listing off the wonders of the Tudor monarchy, with a pointed emphasis on how blessed England is to have Elizabeth I as their queen.[5]

While this order might suggest a clean wrap-up of the narrative – a return to the Tudor version presented at the play’s beginning – preceding it with a version that counters Richmond’s dismissal of Richard as a traitor creates a subversive moment within the play. Along with the earlier moments of sympathy which the Page creates for Richard, it places the play in an awkward position, seemingly both confirming preexisting prejudices against Richard while also undermining them. Ultimately, I would argue, the play subverts audience expectations of who Richard should be, leading, in turn, to a (most likely unintentional) subversion of the Tudor narrative depicting Richard as a malevolent tyrant king.

We invite audiences coming to our production next Friday to consider which version of the narrative they believe: is Richard the figure of Tudor legend? Or, possibly, do we need to re-visit (and re-vise) our understanding of Richard III?

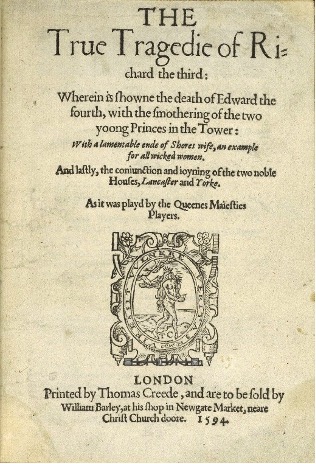

[1] The True Tragedie of Richard the third: Wherein is showne the death of Edward the fourth, with the smothering of the two yoong Princes in the Tower: With a lamentable ende of Shores wife, an example For all wicked women. And lastly, the coniunction and ioyning of the two noble Houses, Lancaster and Yorke: As it was playd by the Queenes Maiesties Players (T. Creede and W. Barley, 1594), Carl H. Pforzheimer Library, 901, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, STC 21009, A3v.

[2] B. Walsh, Shakespeare, the Queen’s Men, and the Elizabethan Performance of History (Cambridge UP, 2009), 84.

[3] True Tragedie, H3v.

[4] R. Stefanek, “‘A Neighbour, Hedges Haue Eyes, and High-Wayes Haue Eares’: Travelling Players, Travelling Spies in 1 Henry IV and The True Tragedie of Richard the Third,” Quidditias: Online Peer-reviewed Journal of the Rocky Mountain Medieval and Renaissance Association 22 (2012): 195.

[5] True Tragedie, I1v.