The night before Agincourt, Shakespeare’s Henry V contemplates what separates a king from the men he rules. “And what have kings that privates have not too,” he ponders, “Save ceremony, save general ceremony?”[1] Ultimately, he decides, the symbols of a king’s rule, combined with the ceremony that goes along with them, prevent a king from being able to enjoy his life like any common man.

Henry’s soliloquy presents playgoers with an example of the ways in which items become imbued with symbolic power. This concept would have been familiar to an early modern audience; Tiffany Stern notes that “visual signs – clothes, props – were ‘read’ symbolically rather than, as now, naturalistically. They were in many ways the physical versions of metonyms […] just as the word ‘crown’ or ‘throne’ can represent kingship, so, similarly, a stage crown or stage throne could represent kingship.”[2]

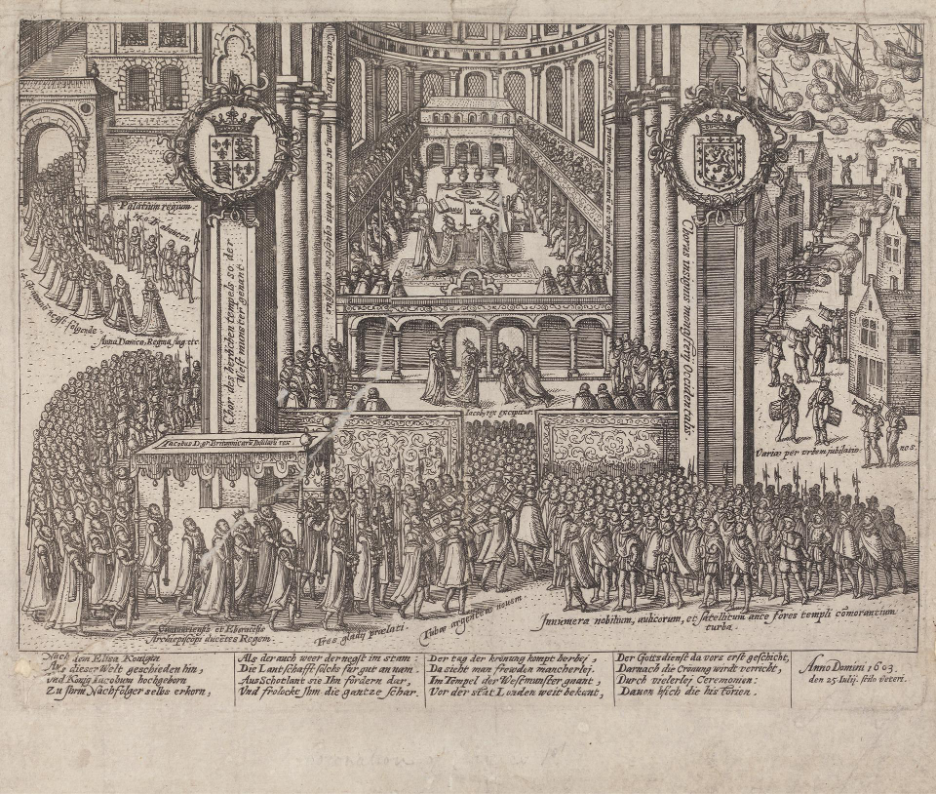

That symbolism extends beyond the stage and into the ceremony of coronation itself. The coronation of a monarch is at once both a significant historical event and a performance that depends upon the presence and use of specific objects to tell a narrative. For kings and queens of England, these items are presented in a specific order, and each is endowed with a specific purpose. Each of these items – from the spurs to St. Edward’s Crown itself – plays a pivotal role in the service, representing different aspects of the expectations for British kings, such as chivalric honor or the blessing and sanctification of the king by God.[3] These “props” are not only individual items, but also representative of something greater than themselves.

Inspired by this theatricality and symbolism, recently brought to the fore by Charles III’s coronation, this season is centered around “prop”-aganda: the roles that these symbols of political power play on the stage. Crowns, one of the most significant, make appearances throughout early modern drama. In history plays, especially Shakespeare’s, the crown is often endowed with a greater meaning: Richard II says that “the hollow crown” is where Death’s court resides; a sleep-deprived Henry IV wryly comments that “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown”; and the title character of The True Tragedy of Richard III describes the crown as “a fatall wreathe, / Of fiery flames, and euer burning starres.”[4] In this season’s plays, crowns not only highlight who is in power, but also become a part of the narrative themselves; they are both prop and costume piece, signifying both the position of the wearer and the more symbolic role that they play.

Beginning in the fall with The Famous Victories of Henry V and Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part 1, we examine two versions of the same narrative: the reformation of “the nimble-footed mad-cap Prince of Wales” into “the mirror of all Christian kings,” Henry V.[5] Both of these stories have central scenes revolving around the taking (or claiming, depending on the perspective) of the crown; in Famous Victories, Prince Henry takes the crown from his sleeping father’s head because he believes him dead, while in Shakespeare’s play, Hal and Falstaff alternate playing the king within a play extempore, with a cushion playing the part of the crown. The questions about crowns and the roles they play continue in the spring with The True Tragedy of Richard III, which centers around the kingship of a man who gained the title, not by right, but by murdering everyone else in his path, and Frederico Della Valle’s La Reina di Scotia, which revolves around the question of rightful queenship and what happens when a queen is “without” her crown – both literally and metaphorically.

This season, the Alabama Shakespeare Project invites you to examine the role of “prop”-aganda in early modern drama. When is the crown a prop and when is it a costume? Do you notice any similarities across the plays in how they discuss the crown? What happens when the crown is worn by someone other than the rightful king? We invite you to join us in these courts of kings and queens as we ponder these questions (and more).

[1] W. Shakespeare, King Henry V, ed. T.W. Craik, 3 Arden Shakespeare (Bloomsbury, 1995), 4.1.235-236.

[2] T. Stern, Making Shakespeare: From Stage to Page (New York: Routledge, 2004), 94.

[3] For the full list of items used at Charles III’s coronation, see The Order of Service of the Coronation of Their Majesties King Charles III and Queen Camilla, https://tinyurl.com/cunn24wj, p. 31-35.

[4] W. Shakespeare, King Richard II, ed. Charles Forker, 3 Arden Shakespeare (Bloomsbury, 2002), 3.2.160-162; W. Shakespeare, King Henry IV Part 2, ed. James C. Bulman, 3 Arden Shakespeare (Bloomsbury, 2016), 3.1.31; The True Tragedie of Richard the third: Wherein is showne the death of Edward the fourth, with the smothering of the two yoong Princes in the Tower: With a lamentable ende of Shores wife, an example For all wicked women. And lastly, the coniunction and ioyning of the two noble Houses, Lancaster and Yorke: As it was playd by the Queenes Maiesties Players (T. Creede and W. Barley, 1594), Carl H. Pforzheimer Library, 901, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, STC 21009, F2v-F3r.

[5] W. Shakespeare, King Henry IV: Part 1, ed. David Scott Kastan, 3 Arden Shakespeare (Bloomsbury, 2002), 4.1.94; King Henry V, 2.0.6.